Within recent years, the creation of electronic music has seen a resurgence of interest in ‘modular’ approaches to sound synthesis and composition. While now, canonical modular systems such as the Moog and Buchla are well known and bear the names of their inventors, the Eurorack format, invented by Dieter Doepfer in the 90s, is a modular synthesiser ‘format’ (this format dictating voltages, sizes, cable types, etc.) that has expanded in scope beyond its inventor, opening out into a cottage industry of developers producing a wide range of modules for the creation and control of electronic sounds.

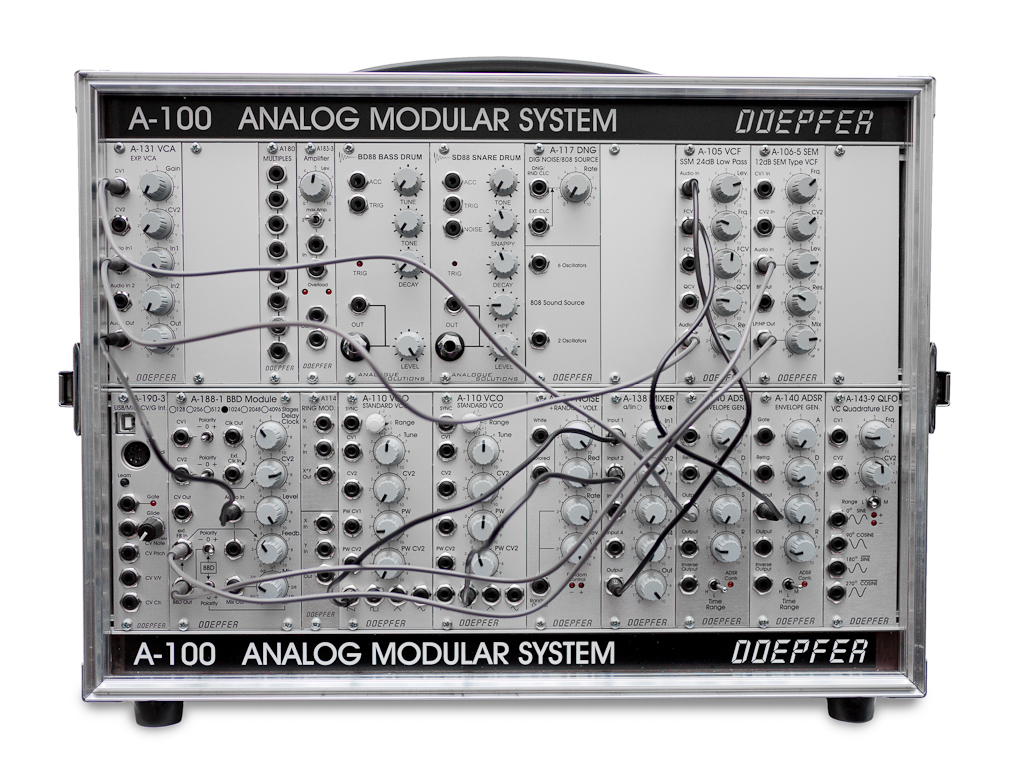

‘Users’ of modular synthesisers can assemble bespoke instruments by combining a range modules from differing developers. A pic ‘n’ mix approach to purchasing a synthesiser (in contrast to buying keyboard based synthesiser that comes in a fully functional and complete form) requires the user to purchase a case, enclosure or box that will house and power their collection of modules. The box has been a distinctive feature of modular instruments since the 1960s when Don Buchla delivered his first Electronic Music System or Buchla Box to the members of the San Francisco Tape Music Centre. It is the boxing or enclosure of modular instruments that I would like to focus on in this blog post.

The boxing of modular instruments has many practical benefits, neatly containing numerous modules, interconnecting wires, power sources, etc., but importantly making the instruments mobile. The portability of modular instruments was an important aspect of their invention in the 1960s, as composers of electronic music sought to open-out not only the range of musical materials and compositional methods available to them, but also to open-out the creation of electronic music beyond the studio. A wider counter-cultural movement within which composers sought exit strategies from the institutions in which early electronic music was made possible (usually universities) saw the desire for a domestication of electronic instruments, for the composition of electronic music to become something that was possible in the home, outside of the institutional confines of the academic music studio. Having developed since the 1960s into a contemporary modular scene, the boxing of modular instruments has continued this drive for domestication. A quick scroll through #modular #eurorack or #buchla feeds on Instagram will reveal a distinctive coffee-table aesthetic and modular instruments surrounded by house-plants and often cats. In addition to portability, the boxing of modular instruments also encourages consumption and collection; cases come in fixed widths, individual modules vary in width, and gaps left in a case are to be filled. As with any collectors display case (Faberge eggs …) unfilled gaps in a case suggest incompletion.

As mentioned above, the Eurorack format is not strongly associated with an inventor, but rather with an aesthetically and operationally (if not demographically) diverse cottage industry of module developers offering distinctive visions for the creation of electronic music. Despite this patchwork of developers, modules and the open-ended nature of modular instrument design, as this scene has matured, dominant developers have emerged. What we can observe in this scene is that as module developers become particularly successful or even dominant, they tend to start producing systems. With the invention of the voltage controlled modular synthesiser in the 1960s, the ‘Buchla box’ was from the outset an Electronic Music System. From the 60s through to the contemporary modular scene we can see that the box and the system often go together. With Buchla and Moog inventing the modular synthesiser in parallel, each largely unaware of the other’s work during early development and experimentation, being apparently ‘the only game in town’ required that Buchla and Moog produce complete systems, self-contained, boxed modular systems produced by a single developer for the creation of electronic music. In the contemporary eurorack cottage industry, the production of complete systems is less of a necessity as the essential components of an electronic instrument can be gathered from any number of developers, allowing individual developers to focus, specialise, to produce something distinctive or simply odd, some modules constituting an art work as much as the musical compositions they make possible. But the idea of the complete system is still clearly a project that has a certain allure.

Examples of contemporary eurorack format systems are the Make Noise Shared System, the ALM System Coupe and the Verbos systems. In each case, the system is presented as a complete, boxed, enclosed collection of modules made by a single producer or manufacturer. The system provides an enclosed and focused statement of the aesthetic and operational logic of a particular developer of manufacturer, a ‘pure’ statement of their creative vision for the world of sound synthesis and electronic music. While this ensures a certain fluidity of operations as the interactions of each module can be guaranteed to a certain extent, I can’t help but feel that the complete system loses something of the open-ended patch-work of compositional possibilities that arise from combining modules from a range of different developers, each embodying a different creative vision. The complete system provides an enclosed image of instrumental stability that is somewhat at odds with the clamorous cottage industry within which these dominant developers have emerged.

The boxing and enclosure of modules is essential to their perception as a system, and if you’ll permit a leap in this meandering narrative, with the notion of a system comes a sense of completion, internal consistency, and the notion of control: musical systems to be controlled by the composer and their authorial vision, but also the wider sense of systems of control that regulate input and outputs as in Wiener’s sense of cybernetic systems for communication and control. Returning to Instagram for a moment, along with the domesticated image of modular synthesis alongside cats and carefully positioned house plants, there’s a recurring theme to many of the images and videos released by developers and users alike: the disembodied (and usually male) hand floating above the controls of a modular system.

Here are a few examples:

Scrolling through these feeds at idle moments, this recurring theme – the hand at the controls, pointing – rang a bell that I couldn’t initially place until this idea of the relationship between the box, system and control glued itself together in my mind. I realised that, once the modular instrument was seen as a system, these images reminded me of the famous image of Le Corbusier’s hand hovering above his model of Paris and the way that architecture in the vein of Le Corbusier has been seen as a system of control and regulation. In both cases, we have the disembodied hand hovering above the system beneath, exercising authorial control over the differing systems they have designed. Amidst the clamorous output and variation of this varied and diffusive cottage industry, the complete system, boxed, contained, presents a vision of stability, of control and order akin to that of the display cases used by collectors of any kind, the production of a system upon which and through which one can produce order, regulate and exercise control.

Focusing briefly on one contemporary developer of ‘complete systems,’ a subtle but interesting shift can be identified in the terms used by Verbos to describe their various complete modular systems: at times the system is described as an ecosystem, an understandable analogy for a system comprising individual components (modules) that interact and influence each other. Yet we can contrast this description of a complete, boxed, modular ‘ecosystem’ with the way that the term ecosystem has already been used in the writing of the composer and theorist of music technology, Simon Waters (2007), not to describe the internal dynamics of single musical instrument of system but a wider interaction between performer, instrument and environment. Where the modular system refers to the content of a box, the performance ecosystem that concerns Waters is opened out onto a wider ecosystem comprising not only the performer and their instrument but also the environment within which both are contained; where the emergence of modular systems entails the enclosure of a complete set of modules in a box, the ecosystem implies a much more open and potentially incomplete or at least indeterminate set of interacting elements: instrument, performer and all that might fall beneath the expansive term environment.

Where the historical emergence of the modular synthesiser occurred amidst the desire for an opening-out of musical potentials, the cyclical return to the complete system entails a level of enclosure, completion and containment, the regulation and control of a system. Yet, within the boxes that house modular synth enthusiasts’ collections, we might spot a number of modules that can be seen to embody divergent pursuits of openness that still motivate many modular designers and manufacturers. At a technical level, this can be seen in the work of Émilie Gillet, sole “product designer, hardware/software engineer, sales person, and customer support representative” of the famous Mutable Instruments collection of modules, a one-person company maintaining a commitment to the principles of open-source technology which has resulted in the proliferation, adoption and development of her designs by other companies and their ‘cloning’ in both software and hardware. The work of modular synth company Rebel Technology can be seen to commit to a similar conception of openness and the commons through the continued production of open-source software and hardware, as well as hybrid digital modules that actively invite the tinkering, designs and reworkings of artists or ‘users’. But, beyond this technological orientation towards commons based or ‘open source’ production, we can identify more artistic senses of openness in modular approaches to composition and sonic practice.

Bridging this distinction between technological and artistic openness is the work of Martin Howse, whose recent modular instruments are both ‘open’ in the sense of being open hardware and free software projects, as well as having found novel ways of encouraging the user, artist or composer to relinquish some of the control that comes along with the notion of the complete modular system. Howse’s modules seek to provide a source of corruption and contagion within the modular enclosure, opening compositional control and intention onto diverse sources of uncertainty. Howse’s ERD/ERD Necromanteion module, for example, “places a small block of earth sourced from three Ancient Greek Oracles of the Dead into the Eurorack circuit”. The introduction of earth (literally soil) into the modular system has a corrupting influence upon authorial control, introducing noise and a new source of uncertainty into a modular synth. Creating a further opening in a modular system, Howse’s ERD/BREATH module has the highly unusual function of providing a heat source within a modular synth allowing the user to heat and burn materials, thereby producing smoke and a heightened interaction between performer, instrument and environment as in Water’s conception of an expanded performance ecology. Even when these unusual kinds of input and output are not included in Howse’s modules, the algorithmic inner workings of his modules often have an unpredictable nature, resulting in the modular synth becoming an instrument over which one exercises influence rather than control. Inviting earth, heat and smoke into modular synthesis sees a shift from the complete and contained system to a punctured, corrupted or incrementally opened modular instrument with increased interaction between performer, instrument and environment, a shift from system to eco-system to use Waters’ terminology again.

The modular way of thinking can be identified in a wider field of contemporary sonic practice, not just as an approach to instrument design and technological development, but as a mode of composition that is distinctly ecological in its open and ‘unboxed’ modularity: examples of this modular approach to composition can be seen and heard in the work of artists such as Kanta Horio and Rie Nakajima. Putting aside, for the sake of brevity, the significant differences between these two artists, we can see that common to both is the creation of modular environments or ecosystems where mobile, resonant, vibrating, buzzing, moving objects are interconnected to produce a composition over which, or rather within which, the artist can exert influence if not complete control.

Here, the neatly boxed modules of modular synthesis (the oscillators, LFOs, envelope generators and so on) are swapped or supplemented with motors, wires, every day ‘impoverished’ objects and materials with alluring sonic qualities, the internal consistency and completion of the modular system opened out into an ecologically open and incomplete network of interacting elements wherein artist, instrument and environment are at times of equal importance.

What hopefully comes across in this short article is a sense of how the ‘modular’ functions in diverse ways within electronic music and related areas of sonic practice as an approach to the composition of music, instruments and networks of interacting objects. The contrast I’ve attempted to establish between enclosed modular collections, ‘complete systems’ and the various openings made within modular enclosures by developers seeking openings onto the commons or the opening of modular composition onto uncertainty through greater interaction between instruments, performers and environments, is intended to begin exploring how modular approaches to musical and sonic practice have historically been subject to oscillations between completion and incompletion, control and influence, enclosure and openness, systems and ecosystems.