Thousands of college instructors, after doing their job for the last year primarily from home and via video, are back to teach in real classrooms and lecture halls this fall. Instead of seeing their students locked into separate Zoom tiles on screen, they finally face them head-on again, physically present. Little about this, however, feels like a return to the old normal. Many institutions wisely mandate students to wear masks, a few like my own permit instructors to take theirs off as long as they maintain six feet distance in class. Some instructors are quick to lament that they, much to their embarrassment, at first fail to recognize students they had taught online just a semester earlier. But the perhaps biggest challenge of this new situation concerns the acoustical dimensions of student-teacher interactions, the often-neglected importance of sound, voice, and hearing to any pedagogical setting. It in my view indicates a profound need to retune our aesthetic and politics of academic listening.

The Ionian Greek philosopher Pythagoras of Samos was said to teach his students hidden behind a veil. The point of this practice was to center his students’ attention entirely on the content of his speech. The veil allowed Pythagoras’s teachings to reach his students’ minds in their presumably purest form and not distract the pedagogical work of reason with the appearance of the philosopher’s body or the physical movements of his lips. Though no historical documents exist to substantiate Pythagoras’s unique teaching technology, his employment of a veil—a full body mask, if you wish—inspired multiple generations of 20th and 21st-century sound practitioners and critics to advocate the power of so-called acousmatic sounds: sounds whose sources remained hidden or unseen; sounds that shunned the visual, the sight of material mediums originating or carrying their vibrations, in order to reach a listener’s ear most intensely. And it in many ways continues to inform our understanding of good, that is: attentive, listening today.

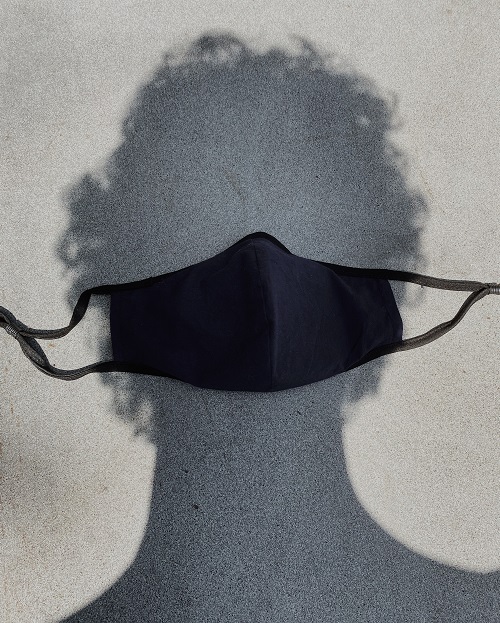

Our teaching setups this fall seem to return at least some of us to Pythagoras’s cave on Samos. The role reversals, however, are as obvious as they shed intriguing light onto the whole desire for disembodied speaking and pure listening. Today’s veils are much smaller, much less comprehensive than Pythagoras’s. They hide the primary source of human sound production, the mouth. They express (legitimate) fears about certain forms of embodiment and corporal contagion. But they of course do not necessarily subtend a new philosophy or pedagogy of disembodiment, a view of philosophy and pedagogy as stages of or for the disembodied. Moreover, and most apparently, in our new order of things we veil the bodies and mouths of our students, move their speaking into the realms of the acousmatic, while the gestures, movements, and sound-producing activities of their instructors remain in full sight. Even stern modernist followers of acousmatic sound, however, will find little reason to rejoice, for whatever we do to uphold at least some elements of Socratic teaching under these conditions, of empowering students to think critically by enabling them to assert their voice in class, is muffled by the materials their face mask. Nothing about the new sound ecology of our classrooms lives up to Pythagorean expectations of acoustical purity. Most of it amplifies rather than contains distraction, causes listeners to wander off into other directions because in veiling the visible it also derails audibility.

It’s easy to nag about the “new normal.” It’s much more rewarding, however, to approach it as a laboratory of insight, an incentive to revise what the past typically took for granted. One possible insight concerns the often-revered role of the acousmatic in sound studies, the praise of sounds without visible sources as a boon to critical listening, a listening that listens most intently because it manages to screen out any other sensory input. As I struggle to identify possible speakers in my class this fall, or as I struggle to attend to their voices in the absence of seeing the movements of their mouths, I cannot help but loath the putative pleasures of the acousmatic: its at once ideological and untenable praise of disembodiment, its rather misguided separation of the audible from the visible, as if one could indeed be clinically kept apart from the other, and as if such a separation could ever succeed in purifying the work of the senses. Today’s inverted veils remind us that perception is always messy, that we hear with our eyes as much as we see with our ears, and that the normative praise of the acousmatic, of acoustic purity, often simply registers a desire to contain the multiplicity of the sensory and to grant one voice, one type of sound, to prevail over or mute all others.

Another possible thought as I try my best to listen to the muffled and hidden voices of my students: sound even in its presumably purest form does not travel in a vacuum. It requires other media—air, vibrating molecules, fiber cables, speaker systems, the resonance of our tympanic membranes—to make its path. Water, as we know when trying to communicate while diving, upsets effective human sound propagation. And so does, to a lesser degree, the paper of facial masks, the layers of cloth designed to protect us and others from contagion. But all things told, water, paper, and cloth are as much media of acoustical transport as the medium of air—just thicker ones, less conductive ones. While they may challenge the operations of “normal” listening, they in fact remind us of the fact that the medium of air is anything but transparent either and that much of what we think about good listening rests on false assumptions about the transparency of air and on norms codifying the receptivity of abled-bodied subjects rarely found in reality. Sound is a medium requiring other media to be heard. It cannot but fail to ever afford utter immediacy or complete purity.

Pythagoras’s veil may witness a curious return in our contemporary ecologies of teaching. But in the end, this return may simply teach us that any hope for or fear of a “new normal” gravely misses our experience as teachers or students today. For nothing about sound, about sound production and dissemination, about hearing and listening, was and should ever be considered as “normal.” What today’s veils reveal is an urgent need to dispel and rethink the norms that guide our thinking about sound—its sensory complexity and messiness, its role within larger economies of attention, and its peculiar function as a medium requiring other media to matter in the first place.

Lutz Koepnick is the Max Kade Foundation Chair in German Studies and Professor of Cinema and Media Arts at Vanderbilt University (Nashville, USA). He has published widely on film, media art, new media aesthetic, sound art, and intellectual history from the nineteenth to the twenty-first century and is the author of Resonant Matter: Sound Art, and the Promise of Hospitality (Bloomsbury, 2021). Koepnick has also co-edited various anthologies on sound culture, new media aesthetics, aesthetic theory, German cinema, and questions of exile.